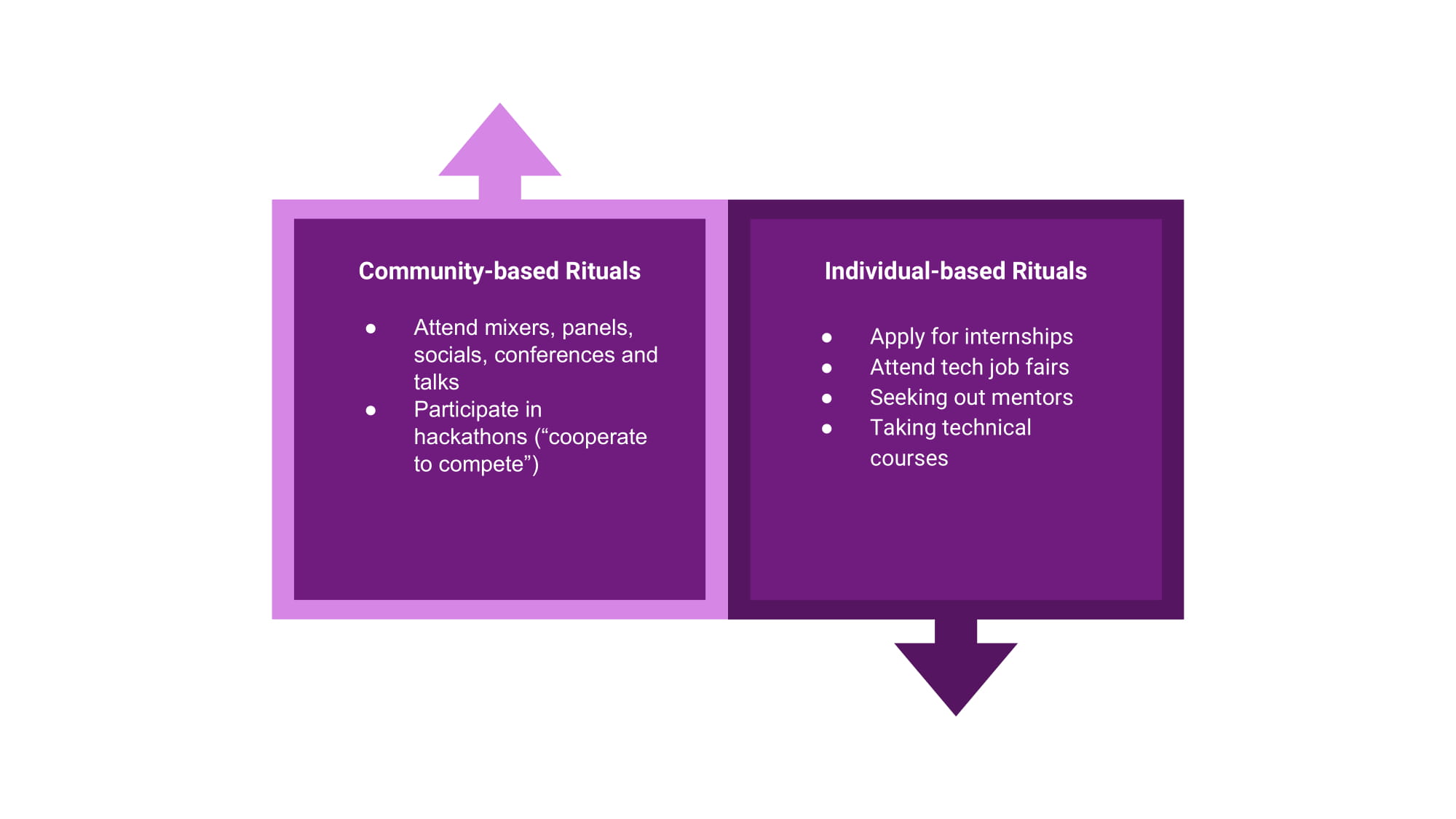

1. We have paid scant attention to the theoretical study of the campus rituals. The ritualistic activities participated by female Stanford students associated with the myth can be divided into two categories: individual-based and community-based.

Here, individual-based rituals refer to actions pursued by individuals in isolation from other members who carry out the same rituals. Such rituals are observed in many cultures, including the Abrahamic religions (baptism, Bar Mitzvah, first recitation of the Quran from memory), the people of Pentecost Island in Vanuatu (Attenborough 1966), and the Arunta of central Australia (see pp. 161-162 of Henrich 2016). Typically, individual-based rituals are "rites of passage" or initiations that serve to award class membership to an individual upon his or her successful completion of the ritual. In contrast, community-based rituals are actions involving multiple individual participants situated in close proximity to one another. These include the church Mass, Sama ceremony, Irakia Awa pig rituals (Boyd 2001, see also p. 173 of Henrich 2016), and Australian Aboriginal song cycles (Birdsell 1979 in this volume, see also p. 131 of Henrich 2016).

In the Figure above, we classify the ritualistic activities of Stanford women in tech using the two labels. Such a distinction could sharpen theoretical analyses of the existence and perpetuation of either of these kinds of rituals at Stanford. For example, many scholars have argued that ritualistic activities bearing characteristics of community-based rituals --- regardless of whether they offer apparent benefits to their practising individuals --- enhance social cohesion and promote cooperative behaviours (Atran and Henrich 2010, Durkheim 1912, Xygalatas et al. 2013). This point of view is so emphasized that contemporary scholars like Armin Geertz and Dimitris Xygalatas have even attempted at finding biological or cognitive explanations, for instance the theories of "biological synchrony" or "increased empathy," the latter of which is the idea that individuals lose sense of themselves and become more empathetic towards other individuals around them as the goals associated with performing the ritual require cooperation or team effort. Empirical studies of Stanford women partaking in the community-based rituals described above may be conducted to validate or challenge this point of view, which may subsequently spur the formulation of new perspectives on ritualistic behaviour.

Likewise, individual-based rituals may be studied by adopting the approach of studying "rites of passage" (van Gennep 1960; Turner 1969, reprinted 2017). Theories about the "liminal phase" and the emergence of social change through rituals can be put to test on the ritualistic pursuits by women in tech at Stanford, using ethnographic methods. Additionally, the approach of viewing rituals as cultural tools (i.e., the cultural evolutionary perspective described previously) may be taken simultaneously, which may allow specific forces that limit or support classical theories to be identified and quantifiable models to be built that could lead to novel insights, backed by data, into the mechanisms and roles of these rituals. (Indeed, there seems to be little work in the literature seeking to merge classical theories with modern data-driven approaches.)

2. Theoretical studies of the myth and the ritual may also benefit from making a distinction between field observations and data obtained from the perspective of the participant ("emic") and from the perspective of the observer ("etic"). Interviews with female Stanford students reveal the significance of the rituals and the meaning of the myth (as per Malinowski) to them, which can be used subsequently to formulate theory. On the other hand, much more data could be collected from the female Stanford population. For example, data on the turn-up rates of students at mixers, student participation in various rituals including sib-fam pairings and hackathons, student interest in tech over time, time spent by students on homework and on rituals, and tech internship applications, may all be useful for analyzing the effects of multiple factors on the perpetuation of the myth. Such data may even motivate the construction of causative mechanisms accounting for the perpetuation of the myth and its associated rituals. The mechanisms may also sharpen the relationships between various factors, and prompt further studies that may yield new data-driven insights.