We saw at the end of Origins that various pieces of evidence seem to suggest

- Women at Stanford are leaning in, getting equal opportunities in tech, and realizing dreams

- Stanford, with all its opportunities and community-building initiatives, prepare a generation of women who will enter tech and balance the gender ratio in Silicon Valley

We know the second myth is false, thanks to (i) statistics and studies on the underrepresentation of women in Silicon Valley and other tech communities more broadly, and (ii) interviews and personal stories from female tech employees and tech entrepreneurs. The first myth is also not entirely true.

We address the claims above in Analysis. Here, we consider how, regardless of whether 1. and 2. are true, such myths continue to create lasting impressions within Stanford. In particular, we explore

- The power of the myth in sanctioning and routinizing particular campus rituals

- The perpetuation of the myth through the exact same rituals

- Other theories for perpetuation of the myth

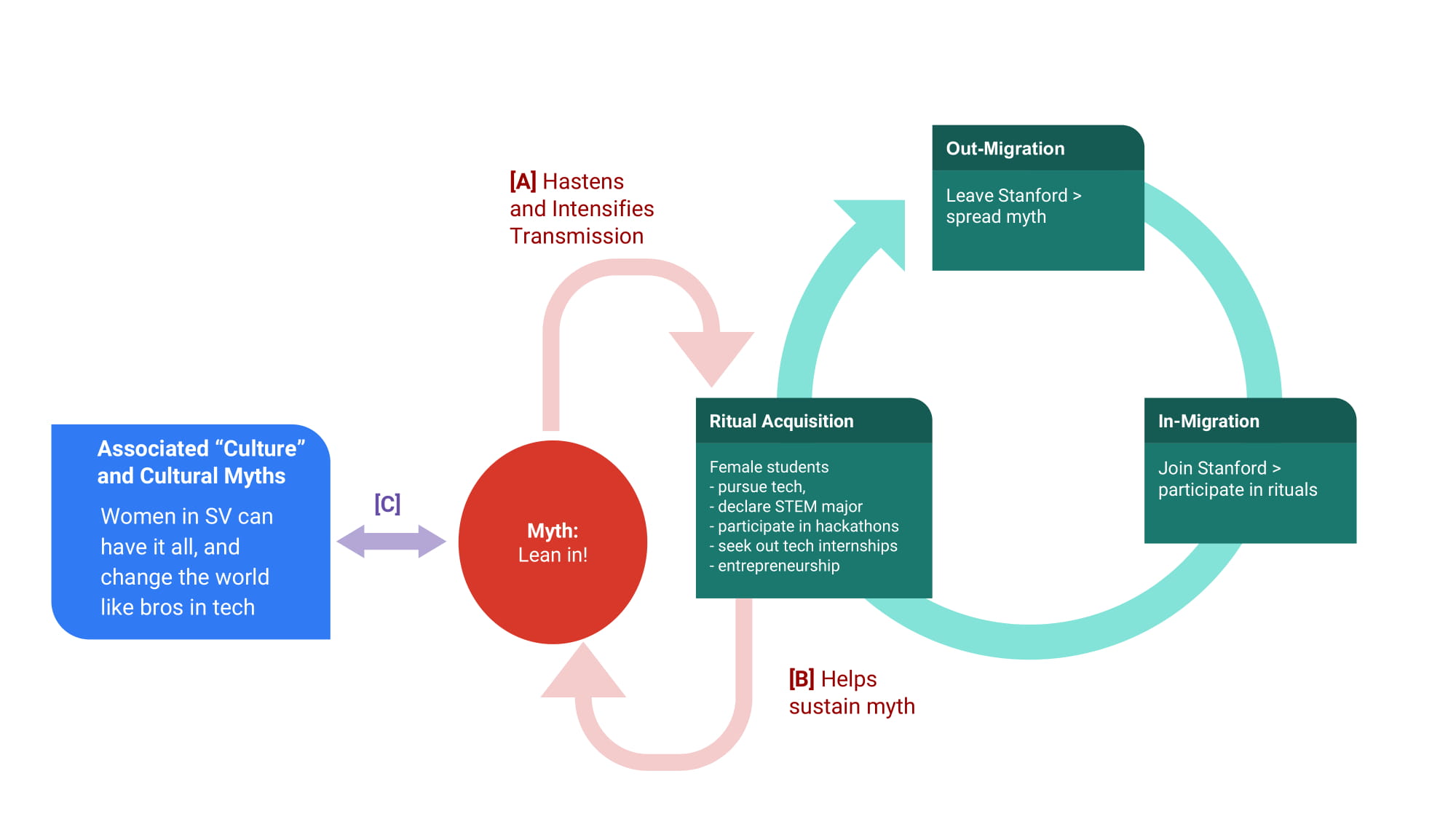

[A]. The pairing of myth and ritual dates back to the Cambridge Ritualists, who thought that myth does not stand by itself but is tied to ritual. Adopting this approach, we consider how the first myth sanctions and may help routinize various campus rituals.

At Stanford, women-focused STEM student groups organize panels, faculty talks, company tours, informal mixers and coffee chats with female professionals --- all of which are attended by many female students interested in tech-related fields. Additionally, some groups pair underclasswomen with upperclasswomen, in so-called Sibling Family ("Sib Fam") programs. As a female mechanical engineering undergraduate (Class of 2019) and member of Stanford Society of Women Engineers puts it,

"I think that a big component of all of them is mentorship and role models. It can be hard to find women in male-dominated fields, so getting advice from someone slightly older than you helps women both prepare for the future and see working in these roles as a real possibility."

We observe that the myth, which many freshly arrived female students are aware of, encourages them to explore and partake in such community-based activities (viewed as rituals) without fear of isolation or not belonging. Various anthropological theories can account for this phenomenon.

Bronisław Malinowski, through ethnographic studies of Melanesian populations, noted the importance of myths (to its adherents) in sanctioning rituals and in maintaining the complex social organization of a population. At Stanford, students who identify with the myth participate in the activities described above. They do so together, out of each and every individual's belief in the myth. The student groups and related events like the Women in Data Science conference and Women in STEM Symposium, in which professional connections between networks of women scientists and engineers are created, testify to the formation and maintenance of social relations among Stanford women in STEM that are centered on the myth.

Another point of view originates in the etiological approach, which sees myths as "primitive science" offering heuristic explanations for natural phenomena. The myth now plays the role of an explanation for the apparent success of Stanford students at obtaining jobs in Silicon Valley. Because of the warm ties between Stanford and Silicon Valley, anyone from Stanford (male or female) who works hard ("leans in") is set to land a job in a tech company and have their future set in stone (because it's Silicon Valley, the land of wealth, creation and innovation). The ritualistic activities are then viewed as strategies making up the "primitive scientific theory," with strategic rules learned from the accumulation of cases of individual success.

The etiological approach actually helps pave the way for modern evolutionary approaches, which may offer a more illuminating and useful account. Several cultural evolutionists (e.g., Joseph Henrich, Michael Muthukrishna) have proposed theories for the existence and persistence of religion, and ground such theories on ethnographic and historical data as well as biological and psychological approaches (see e.g., Atran and Henrich 2010 and The Database of Religious History). Broadly speaking, these theories view religion as a particular cultural innovation, which, like other human innovations, confers biological advantages to human populations and ensures their survivability. Adopting such an approach, rituals can be viewed as cultural tools, a collection of rituals a cultural package, and myths posthoc narratives seeking to "storify" --- i.e., make sense of --- the cultural package. Under this framework, the myth exists as a narrative, refined over multiple generations of Stanford students, explaining and summarizing the steps taken by women at Stanford that have led to their success in the tech world. The steps themselves are organized and routinized as rituals, the activities we described earlier. Precisely because of its explanatory value (i.e., connecting a series of activities through a common synopsis), the myth ensures the continuation of its constituent ritualistic activities (which are understood as logical constituents of the explanation). In other words, the myth not only summarizes the rituals but hastens their adoption by (or transmission to) new Stanford students, because its credibility has stood the test of time. This approach is consistent with Jonathan Z. Smith, who described how the routinization of an activity depends crucially on the sacrosanctness its occurrence. ("Ritual is an exercise in strategic choice," wrote Smith.) Indeed, the sacred nature of landing a job and making a difference in Silicon Valley may be sufficient for a series of activities to be routinized and subsequently refined over multiple generations.

[B]. The evolutionary approach also elucidates the causative relationship between the rituals and the myth. As described earlier, the myth functions as a narrative summary of the ritual package. As more and more women at Stanford participate in the ritualistic activities and build a community, the more effectively and quickly technical skills and beneficial strategies are transmitted and acquired. The increase in number of competent women is then associated with a higher incidence of Stanford women in STEM joining the tech workforce, which sustains the myth of "leaning in" and "having it all" (see bottom pink arrow in Figure above).

Looking further, the evolutionary approach also points to multiple mechanisms under which the myth is sustained through the spread of its rituals. Apart from the myth being spread within Stanford, women who leave Stanford and work in tech industries around the world are carriers of the ritualistic package and can spread the package with its narrative myth to individuals who have not set foot on Stanford (see green cycle in Figure above). In other words, women who aspire toward tech careers meet role models, who are the successful Stanford women, and receive the ritualistic package through its mythical synopsis. These individuals may end up moving to Stanford for their studies, and because they are already familiar with the rituals and possess the tools and beneficial strategies, have a headstart in pursuing a tech career. There may be some evidence of this mechanism in the growing number of female Stanford students interested in or even pursuing tech.

There is one caveat to this approach. It hinges on the assumption that the rituals associated with the myth are sufficiently refined that they capture only the essential steps guaranteeing a Stanford female student's fulfillment of "leaning in" and "having it all." As Wendy Doniger draws from studies of the Hebrew Bible and Hindu mythology (Doniger 1999), myths have a super-microscopic and sub-telescopic character: they sit between individual narrative and generalized theory. Likewise at Stanford, the myth may have emerged from multiple individual success stories, which have high variability both in terms of the ritualistic features relevant to time spent at Stanford and perhaps even higher variability for features that go beyond Stanford (e.g., work after graduation). As we will see in Analysis, multiple nuances in the path to success in tech, as well as systematic biases existent in the current male-dominated tech community, challenge the effectiveness of the rituals in helping women attain their aspirations in tech and, therefore, the veracity of the myth.

[C]. Apart from its cyclical relationship with ritualistic activities on campus, the first myth may exist to validate associated myths in Silicon Valley (see purple bidirectional arrow in Figure above). Because of the revered status of Silicon Valley and Stanford's history of creation and partnership with tech companies in the valley, myths about Silicon Valley and Stanford often reinforce each other, which blurs the distinction between the two entities and allows the reputation and strengths of one community to raise the profile of the other.

In this case, the myth of Stanford women leaning in and having it all may serve to validate the greater myth about Silicon Valley being welcoming to women. For simplicity, we call this latter myth the SV Myth. The SV Myth seems plausible given the growing opportunities for and participation by women in tech (e.g., Grace Hopper Celebration, women's LinkedIn profiles listing tech internships, stories shared online or within communities, all of which may hype up the presence, representation and inclusion of women in the tech community). As more female students graduate with technical degrees, more women are expected to join tech companies just because the degree prepared them for such jobs anyway. Moreover, Silicon Valley, idolized as a "magical entrepreneurial brew" and situated in the "Wild West" (Kenney 2000), ought to be progressive and different than other "mainstream" cultures. So women ought to have the best of both worlds by being in tech and being in the valley.

As we saw at the beginning of the section all of this is false (thanks to statistics, investigative journalism, and personal anecdotes by veteran Silicon Valley women). Regardless, for people who are ignorant of the data and anecdotal evidence --- presumably largely non-Americans or Americans unfamiliar with tech culture but are interested in tech --- the SV Myth offers a plausible narrative about women in the valley that is consistent with the all-powerful image of innovation and change that defines the valley. The first myth, through its clause being consistent with the clauses of the SV myth, therefore holds water as long as the SV myth is thought to be true. (Indeed, imagine a simplistic sequence of steps: first myth leads to woman interested in tech benefiting immensely from opportunities and resources offered at Stanford, then lands job at progressive SV, which welcomes her.)

§

We have presented various theoretical approaches that could explain the perpetuation of the first myth. Our approaches describe multiple causative relationships, both from myth and ritual and from ritual to myth. Our third explanation also highlights the possibility of the myth being perpetuated for different reasons depending on the population considered --- namely, whether it comprises Stanford students who engage in the rituals associated with the myth, or comprises outsiders who are aware of the myth but do not practise the associated rituals. On this new page, we suggest other approaches that may refine our current theoretical discussion.